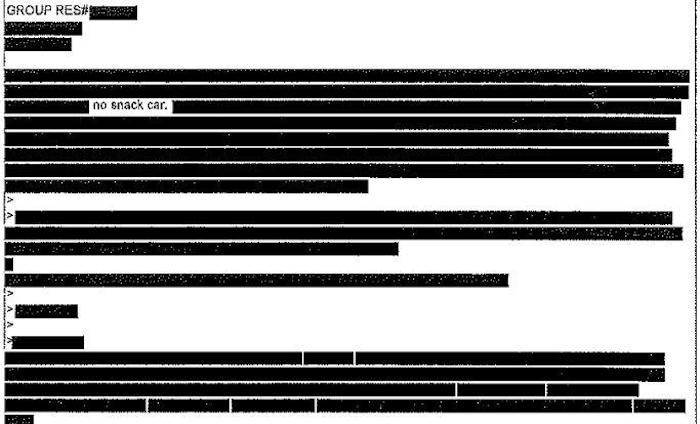

This almost entirely-redacted document was released to a MuckRock user who had asked to see complaints related to Amtrak trains' lounge cars.

Fun with FOIA: How MuckRock Is Making Public Records Requests Cool

Read this article in

Public records sometimes say the darnedest things. One example: A declassified memo from 1977 shows that the NSA wondered if psychics could nuke cities so that they became lost in time and space (yes, like in the post-apocalyptic anime Akira). Other times, it’s what they don’t say — like when the FBI found it necessary to redact the name of Superman’s alter-ego, Clark Kent.

We know about these great tidbits thanks to the work of MuckRock, a nonprofit organization (and GIJN member) that helps journalists, researchers, activists and regular citizens file records requests in the United States. While there few things sweeter than a successful request for government records, making these requests be complicated and time-consuming — not to mention, well, tedious. MuckRock, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has been working for the past nine years to make the process a lot more fun.

Not only does MuckRock help simplify the FOIA process — starting at $20 for four requests, they’ll help craft and send queries, follow up with the agencies and host the materials — their news site features serious investigations as well as humorous articles, all based on government documents.

MuckRock’s lighthearted, irreverent tone — which revels in the absurd, but avoids snark — is no accident. Executive editor JPat Brown, who came to the organization from a background of humor writing for alt-weekly magazines, is on a mission to show readers that you can actually have fun with FOIA.

“If you don’t have a sense of humor about this stuff, then you can sort of go crazy,” says Brown, who was once told that one of his FOIA requests would take about 132 years to complete (but who stresses that more often than not, he gets good responses). “We try to find different ways to make it accessible, to bring it into the house and make it alive and real.”

When Brown says “into the house,” he means this literally. A recent article challenged readers to try their hand at cooking a Soviet-era borscht recipe that MuckRock found in declassified CIA documents. The winner of the contest live-tweeted his experience.

https://twitter.com/Lollardfish/status/1089282392488067072

“I also found Mao Zedong’s workout routine, so I’ve been trying to do it every morning, and I figure I’ll write a story after doing it for a month to show what ‘Body by Mao’ is like,” Brown says. What exactly does the workout entail? “Well, you’re supposed to punch your body to accelerate blood circulation, and then there’s 10 minutes of dancing…” (Since this interview took place, Brown has published his story. And yes, it was titled ‘Body by Mao’.)

Aside from recipes (there’s also one for fudge) and workouts, other recurring themes in MuckRock’s articles include:

- Head-scratching replies to requests, like when the FBI could neither “confirm nor deny” the existence of investigations into darknet investigations — that it confirmed were ongoing;

- Weird history, like the time Timothy Leary trolled Ronald Reagan;

- Hilarious complaints, like the multitude of gripes made to the Federal Communications Commission about Super Bowl halftime shows being “Luciferian” and “pagan,” or the heavily-redacted complaints about Amtrak trains’ lounge cars that include cliffhangers like “[Patron] stated again that his sausage was cold & his wife had black curlie hair in her REDACTED.”

- Creepy/cute photos (like this nightmare-inducing “Picture of a Man” or this adorable stray kitten);

- Absurdly-redacted documents, like when the CIA redacted the name of its own cafeteria.

“I think public records is only going to work if the public understands it and supports it and knows about it,” says Michael Morisy, MuckRock’s chief executive and co-founder. “If you find out about this [freedom of information] law because of something silly, that’s a lot of times an easier way to get into this and get excited about it than if you focus on the legalese aspect.”

The staff of MuckRock. From left to right: Jessie Gomez, JPat Brown, Mitchell Kotler, Kiera Murray, Beryl C.D. Lipton, Dylan Freedman and Michael Morisy.

A large section of the site is dedicated to FBI archive materials, with articles about who the bureau surveilled and why. These stories often serve up interesting tidbits, like this one: “Documents from the Federal Bureau Investigation reveal that as part of COINTELPRO, the Bureau once attempted to impersonate a redacted Black Panther Party official in forged letters to expel ‘fringe’ members. That plan was ultimately never brought to fruition, but not due to any last-minute attack of conscience — the FBI had simply run out of stationery.”

The FBI files offer peeks into the lives of disparate characters ranging from Albert Einstein to Malcolm X to Zsa Zsa Gabor.

“Anytime someone dies, you can request their FBI files, so as long as people keep dying, there’s always going to be a lot of material,” says Brown.

One of MuckRock’s goals is to foster a community of FOIA fans. While it engages users by asking them to collaborate on serious topics — for example by using its crowdsourcing tool to comb through the Mueller Report — it also engages them through fun and games, like the aforementioned borscht cooking contest or the popular FOIA March Madness.

Now in its fourth year, FOIA March Madness works a lot like the US college basketball version of March Madness, where participants bet on teams in the NCAA Division I Men’s Basketball Tournament, except in this version, instead of basketball teams, the brackets consist of 64 federal agencies. MuckRock sends the same request to all the agencies — this year, it asked for data about the agencies themselves — and participants bet on how quickly agencies will reply. MuckRock puts the agencies in brackets, and each week, advances them based on if they get back to them and whether they release any information.

“Agencies repeatedly tell us that FOIA March Madness is their favorite thing, and that they look forward to it every year,” Brown says. “Some agencies take it super seriously — the SEC [Securities and Exchanges Commission] actually made their own award for themselves after they won. Of course, some of the agencies are always going to be bad sports about it, like the CIA and the FBI. But a lot of people [at agencies’ FOIA offices] are actually in this line of work because they want to be doing it.”

The agency that came out on top of FOIA March Madness in 2018, the Securities and Exchange Commission, created a plaque with a rock on it. They have pledged to give it to this year’s winners. Photo: Courtesy of MuckRock

FOIA March Madness isn’t easy, says David Cuillier, who is president of the National Freedom of Information Coalition: “I used data, crunched it and picked agencies based on past performance. But it looks like I didn’t do that well, which tends to confirm my thinking in that it’s kind of hit-and-miss depending on which FOIA officer you get that day!”

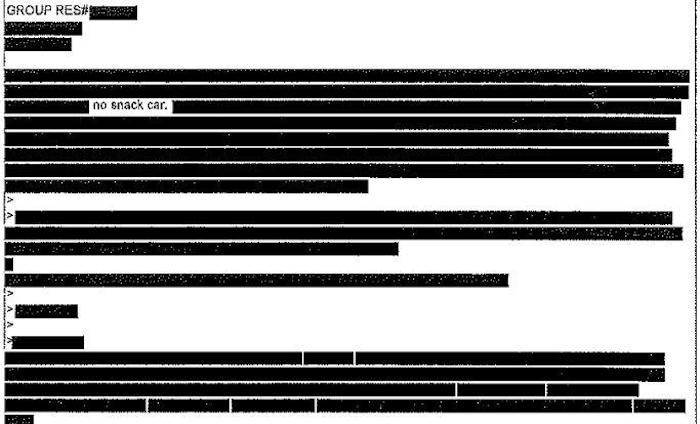

Participants whose picks came out on top win packs of MuckRock swag, which is not just your typical tote bags and mugs. Well, they do have mugs, but they’re magical unredacting mugs. MuckRock’s merchandise is full of jokes for public records aficionados, like T-shirts bearing the major US records laws’ acronyms; stickers that read “Always Be Filing”; and “Black Bar” T-shirts (a spin on the logo of punk rock band Black Flag).

They even have poetry magnets full of words frequently found in replies to requests (including, of course, the words “can,” “neither,” “confirm,” “nor,” “deny”).

“We’d joke sometimes that these letters sounded like Mad Libs, where the agency is sitting around saying, ‘um… complex processing, um… neither confirm nor deny’, like they’re jumbling up a bag and pulling up these phrases one at a time,” Brown said. “So we decided to have fun with that and create poetry magnets.”

Recently, MuckRock hosted an event to celebrate Sunshine Week, and MuckRock being MuckRock, it wasn’t just any old talk — it was a Transparency Science Fair, complete with booths, interactive exhibits and prizes.

The tools, the articles, the games, the swag, the events — and of course social media channels and newsletters, too — it’s all part of MuckRock’s drive to build a community of requesters. And it seems to be working.

“Muckrock is helpful because they put out newsletters about successful releases of information that can spark new ideas or questions,” says Anthony Fisher, politics editor at Insider and Business Insider, and a regular user of MuckRock’s requesting service. “I also follow them on Twitter, and every once in a while they’ll show you something fun, like an FBI file from the sixties — something absurd like John Lennon’s FBI file. I think it’s a healthy thing for people to look back at the supposed glory days of the past, and you realize, oh, right, the government was always stretching its power and doing things that they don’t want you to know about.”

Another regular is Jasper Craven, a freelance journalist who specializes in covering the military and veterans. He did a college internship at MuckRock five years ago, and has continued using the service since.

“There’s something fun about the service, sort of like a social network,” Craven says. “You get notifications when there are updates to your requests, and there are requesters I follow. Oftentimes if I’m trying to structure a certain request, I’ll look through MuckRock’s repository of archived requests and crib language from someone who’s really good at this. You can also look at how others are engaging with this law, and get inspired.”

Requests and the resulting documents are publicly posted on MuckRock’s site, though users can opt to embargo their requests.

“MuckRock’s process for submitting requests is probably the easiest out there for someone just getting started,” says Nate Jones, Director of the Freedom of Information Act Project for the National Security Archive, a nonprofit that collects declassified records.

MuckRock operates with a staff of seven full-time employees. According to Morisy, its budget for 2017 (the most recent year for which finalized financials were available) was just under $300,000. About half of MuckRock’s funding comes from grants from the Democracy Fund, the Knight Foundation, the News Integrity Initiative, and the Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence Initiative. A quarter comes from payment for MuckRock’s services, and the remaining quarter comes from miscellaneous sources like individual donations and merchandise sales (including the sales of two books they’ve authored about the FBI files of writers and scientists).

MuckRock works with US government records, so most of its users are American. However, its staff encourages people living in other parts of the world to request records, too.

“The US has influence and gathers data around the globe,” notes Morisy. “And sometimes that can be useful for things like digging into environmental data — maybe the US consulted on environmental projects abroad and you can get some data from the Environmental Protection Agency, for example, that you’re not going to get out of an agency in your country because its laws are different.”

Come for the fun articles, stay for the data. But if you’re not ready to file a request, that’s OK, too.

“We want more people filing requests, but we also want more people just supporting and understanding the value of these laws,” says Morisy. “Because that’s really at stake here — increasingly, people are skeptical of government, but also skeptical of oversight of government, and so you talk to a lot of people who say, ‘Well, if the government says that we don’t have a right to know, then who am I, an ordinary citizen, to push back against that?’ I think that’s a very dangerous mentality.

“We have to go out and educate people and say: If in a democracy you’re the government’s boss, then you have not just a right but a responsibility to understand what’s going on. So I think making this accessible, demystifying this process is part of how we build that support.”

Gaelle Faure is GIJN’s associate editor. Previously, she worked for France 24, where she specialized in social newsgathering and verification. She has also worked as an editor for News Deeply and reported for Time Magazine.

Gaelle Faure is GIJN’s associate editor. Previously, she worked for France 24, where she specialized in social newsgathering and verification. She has also worked as an editor for News Deeply and reported for Time Magazine.